According to legend, an Ethiopian goatherd named Kaldi once noticed that his goats were unusually energetic after eating the red berries of a wild shrub. They ran tirelessly, showing no signs of fatigue.

Intrigued, Kaldi brought the berries to a nearby monastery, where the monks, after brewing an infusion, discovered that the drink helped them stay awake during their long nighttime vigils. Thus, the story goes, coffee was born.

Beyond folklore, the origins of coffee trace back to Ethiopia, where its beans were consumed in various forms long before they became the beverage known today. However, it was not Ethiopian Christians who spread knowledge of coffee to the world—it was Arab Muslims.

Sufi Mystics and the Spread of Coffee

In 15th-century Yemen, Sufi mystics transformed coffee into a cornerstone of Islamic spiritual practice. They used it to sustain wakefulness during dhikr—the meditative recitation of divine names—and to enhance focus.

The drink quickly gained popularity, spreading from Yemen to the religious and commercial hubs of Mecca and Cairo. Coffee was imported from Ethiopia through a Yemeni port that would soon become synonymous with the beverage: Mocha.

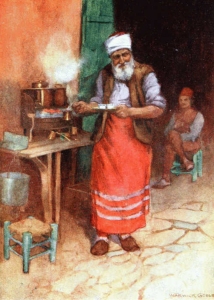

The Arab Coffee Tradition

Coffee became deeply embedded in Arab and Muslim culture, not only in religious settings but also in social life. It symbolized hospitality and generosity, and to this day, serving coffee is a sign of respect and welcome in family gatherings, tribal councils (majlis), and diplomatic meetings.

Its preparation follows a meticulous ritual. Beans of Coffea arabica are roasted, ground, and slowly brewed in a dallah, a long-spouted metal coffee pot, before being served in small, handleless cups known as finjān. In some regions, the brew is infused with spices such as cardamom, cloves, or saffron.

There are unspoken rules surrounding coffee etiquette. The host traditionally serves the first cup to the highest-ranking guest. Accepting the drink is a gesture of courtesy, while refusing without a valid reason may be seen as disrespectful. Customarily, three cups are consumed—drinking only one may signal disinterest, and shaking the cup upon returning it indicates that no more is desired.

Controversy and Prohibitions

Despite its deep cultural roots, coffee was not universally welcomed in the Arab world. From its earliest days, some religious and political leaders viewed it with suspicion. As coffeehouses emerged as spaces for discussion and debate, authorities feared they could foster dissent.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, several attempts were made to ban coffee in Muslim cities, citing concerns that it stimulated critical thought and encouraged questioning of authority. However, these restrictions ultimately failed, and coffee continued to spread across the Islamic world.

Coffee Reaches the West

Coffee arrived in Europe in the 17th century through Venetian traders. Initially, its Muslim origins led some Catholic clerics to call it the “devil’s drink.” According to legend, they urged Pope Clement VIII to ban it, but after tasting it, he reportedly declared that it would be a shame to leave such a delightful beverage to non-Christians.

With papal approval, coffee gained widespread acceptance in Catholic regions, especially among monks who, like the Sufis, valued it for its ability to keep them alert during nocturnal prayers.

However, coffee met resistance in Protestant countries. In England and Germany, it was seen as a threat to the dominance of beer, the traditional beverage. Early coffeehouses became hubs of intense philosophical and political debate, prompting some rulers to attempt to close them.

In 1675, King Charles II of England ordered coffeehouses shut down, fearing they were breeding grounds for conspiracy. Despite such opposition, coffee eventually took root in Europe, and by the 18th century, it was firmly established in intellectual, commercial, and religious circles.

A Lasting Cultural Legacy

Today, Arab coffee remains a symbol of identity and social cohesion in the Middle East. Its preparation and customs have been recognized by UNESCO as part of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

Despite centuries of controversy and adaptation, coffee has proven to be more than just a beverage. It is a bridge between spirituality and daily life, a testament to the power of hospitality, and a catalyst for reflection and intellectual exchange.

In an increasingly globalized world, Arab coffee continues to remind us that some of the best conversations and moments of connection begin with a steaming cup.

A 17th-century Arab proverb advises:

“Drink coffee without regret. Its aroma calms the nerves, and its consumption eases life’s troubles.”