In the limestone beneath Paola, a densely built suburb just south of Valletta, lies one of the oldest ritual sites in the Mediterranean. The Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum, a subterranean complex excavated over 5,000 years ago, is an enduring testament to Malta’s early ceremonial landscape—an intricate world of belief, stone, and silence. Long before Christian churches defined the island’s skyline, structures like the Hypogeum shaped the archipelago’s spiritual architecture, rooted deep underground.

Comparable in age and ritual complexity to Stonehenge or Göbekli Tepe, the Hypogeum stands as part of a larger tradition of prehistoric megalithic construction in Malta. These spaces were created not as fortifications or dwellings, but as monuments to ritual, burial, and collective imagination. Their placement, orientation, and design point to a highly developed ceremonial culture—one that laid the foundation for later forms of sacred expression.

A Chambered World Beneath the Surface

Discovered in 1902 during construction work, the Hypogeum (Ipoġew ta’ Ħal-Saflieni) is the only known prehistoric underground sanctuary of its kind in Europe. Carved directly into Malta’s soft globigerina limestone, it spans three levels and descends more than ten meters below ground. Archaeologists date its use to between 4000 and 2500 BCE.

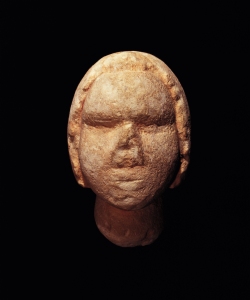

Its chambers follow a circular and organic design, with smoothly curved walls, acoustic hollows, and symbolic markings. Spiral motifs and red ochre traces appear throughout. The site once held the remains of over 7,000 individuals, along with carved figurines, animal bones, shells, and beads. One of the most well-known finds, the so-called “Sleeping Lady,” suggests ritual gestures of repose or regeneration. The dead were not simply interred—they were positioned within a space designed for recurrence, transformation, and continued presence.

Unlike the monumental temples at Mnajdra or Tarxien, which mark solar cycles and stand in the open air, the Hypogeum creates an interior experience—one shaped by darkness, resonance, and physical descent. The layout mimics above-ground architecture, suggesting that these chambers were not isolated structures but embedded within a wider ceremonial system.

Megalithic Malta and the Structure of Belief

The Hypogeum belongs to the same cultural horizon that produced Malta’s extraordinary network of megalithic temples—structures among the oldest freestanding stone buildings in the world. Sites such as Ġgantija in Gozo and Ħaġar Qim on Malta were constructed with precision and scale, indicating coordinated effort and a shared symbolic framework.

These sites served as fixed points in a landscape shaped by cycles of life and death, aligned to seasonal movements and embedded with meaning. The presence of altars, carvings, and passageways in both above- and below-ground spaces suggests that ceremonial activity was central to community life. The island’s spiritual traditions, far from being marginal, were foundational to its social and spatial organization.

Ħal Saflieni is not an isolated curiosity. It is part of a continuum that positions Malta as a key node in the prehistoric Mediterranean—a crossroads of trade, movement, and belief systems that predate writing and metallurgy.

From Stone to Chapel

By the first centuries of the Common Era, Christianity began to take hold in Malta, establishing new religious customs, spaces, and narratives. But this shift did not erase earlier understandings of place. Instead, new practices emerged within an already sacralized landscape.

Early Christian communities in Malta often worshipped in underground catacombs. These rock-hewn spaces, especially those in Rabat, echo the spatial language of Ħal Saflieni—chambers, niches, acoustic zones. Later, churches and chapels appeared near or even over prehistoric sites. Such layering of sacred architecture reveals a continuity in how space was consecrated, even as its meanings changed.

Malta’s transformation into a Christian society did not require a tabula rasa. Instead, it absorbed and reorganized earlier systems of orientation, gesture, and place-making. What had once been a chambered tomb became a crypt; what had been a carved spiral became a sacred symbol of rebirth.

A Ritual Legacy

Access to Ħal Saflieni today is strictly limited to preserve the site’s delicate structure and surviving pigments. Entry is granted to a small number of visitors each day under tightly controlled conditions. The atmosphere remains as it likely was millennia ago: hushed, enclosed, and resonant.

While the Hypogeum no longer functions as a ritual site, its presence continues to shape how Malta understands its own heritage. It stands as evidence that the island’s engagement with sacred practice began long before the arrival of institutional religion. The choice to build underground, to mark stone with patterns, to accompany the dead with care and ceremony—these were not casual gestures. They formed a world of meaning in which people lived and died with a sense of continuity beyond the visible.

In Malta, sacred space has always been tied to stone—whether laid flat in a prehistoric chamber or stacked high in a cathedral dome. Ħal Saflieni endures as a structure from deep time, holding the memory of a spiritual tradition that gave shape to the archipelago long before its churches rose.

Malta underground: From Neolithic shrines to Saint Paul’s grotto