In the 16th century, a series of expeditions set out from the highlands of the Andes and the coastal outposts of the Caribbean toward a destination that did not exist – at least, not in the way their leaders believed. The name was El Dorado. It meant different things to different people: a man, a city, a kingdom, a horizon gilded with promise.

The journey into the interior was not only geographic. It was an encounter between two systems of meaning – European and Indigenous – each with its own logic of space, value, and transformation. Along riverbanks and forest paths, the two collided, clashed, and occasionally converged. El Dorado, as it emerged in the historical record, is not simply a European fantasy imposed on American soil. It is a phenomenon born at the intersection of belief and movement – of ritual and ambition – traced through the very landscapes that reshaped it.

A Man Covered in Gold

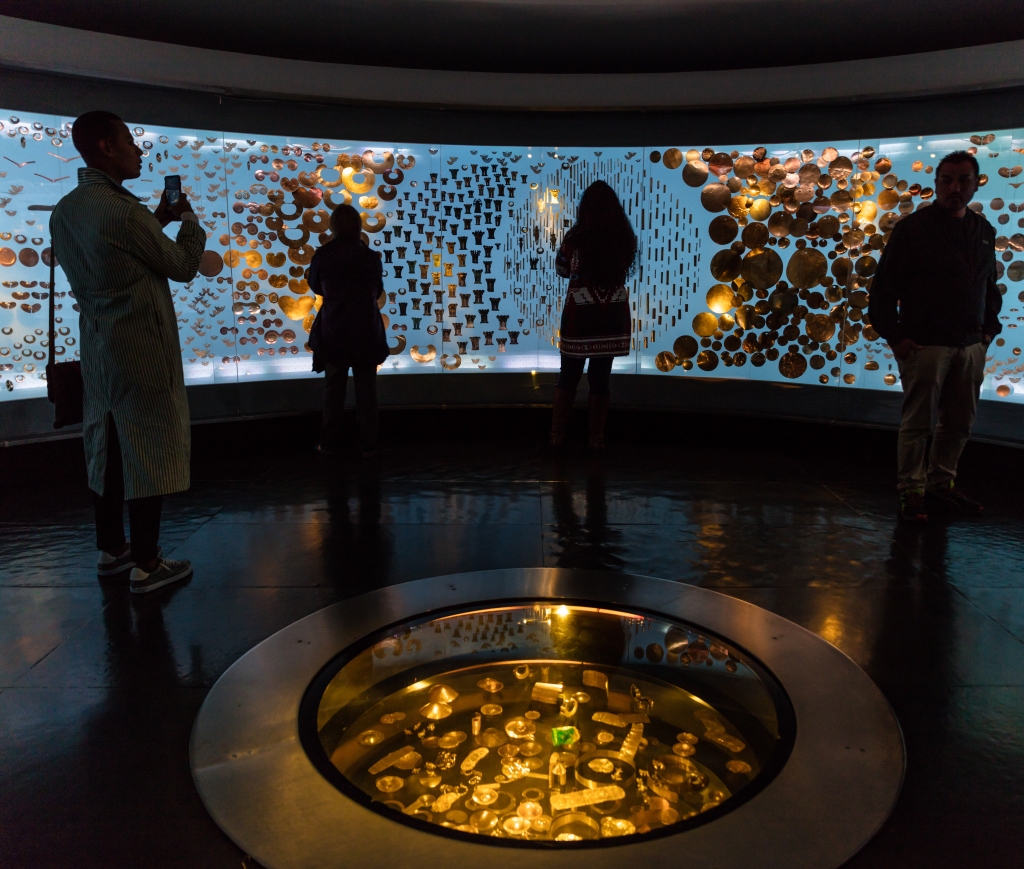

The story began with a ritual. In the highlands of what is now central Colombia, the Muisca people enacted a ceremony at Lake Guatavita to inaugurate their new leader. The zipa, standing on a raft, was dusted with gold and surrounded by priests and offerings. Gold and emeralds were cast into the lake as gifts to the spirits. It was not an ostentatious display, but an ordered rite – bound to cosmological cycles and governed by obligations to the landscape.

When news of this ceremony reached Spanish ears, it was transformed. The gilded man became a legend. The lake became a treasury. Gold ceased to be symbolic; it became proof of empire, fuel for ambition. The Spanish heard in the Muisca rite not continuity, but possibility. Their maps widened.

Descent into the Interior

Expeditions multiplied. In 1541, Gonzalo Pizarro and Francisco de Orellana crossed the Andes with hundreds of men, dozens of horses, and a mission to find the source of wealth they believed lay beyond the mountains. They descended into the Amazon basin, into unfamiliar territory, guided in part by Indigenous allies and captives whose geographies were neither fixed nor meant for European use.

The landscape itself resisted them. Rivers shifted course, food supplies vanished, maps became guesswork. The quest, originally conceived as a march toward a fixed goal, became a moving search through a space increasingly shaped by uncertainty. What the Europeans called wilderness was in fact a matrix of Indigenous territories—lands inscribed with meaning, story, and presence.

For their guides, the journey moved through spaces already connected by kinship, trade, and ceremony. For the Spaniards, these same spaces became a screen for projection. The further they went, the less they understood. But the more they were compelled to believe.

Worlds Entangled

The encounter was not one-sided. Indigenous communities along the expedition routes responded with caution, resistance, hospitality, or strategic evasion. Some used the Spaniards’ hunger for gold to redirect their path. Others offered narratives – true, partial, or calculated – that fed the expedition’s momentum. Stories of powerful cities deeper in the forest circulated from both sides.

El Dorado became a mobile idea, shaped as much by Indigenous information management as by European imagination. It was not simply a myth imposed from without. It was co-produced in the contact zone, where storytelling became survival and distance became strategy.

In this way, the expedition took on the features of a ritual journey, though not in the sense understood by the people it encountered. It passed through thresholds, altered bodies, reordered time. Hunger, illness, disorientation – all reshaped the experience. Like a pilgrimage, it transformed its participants. But unlike pilgrimage, its aim was possession, not relation.

Collapse and Continuation

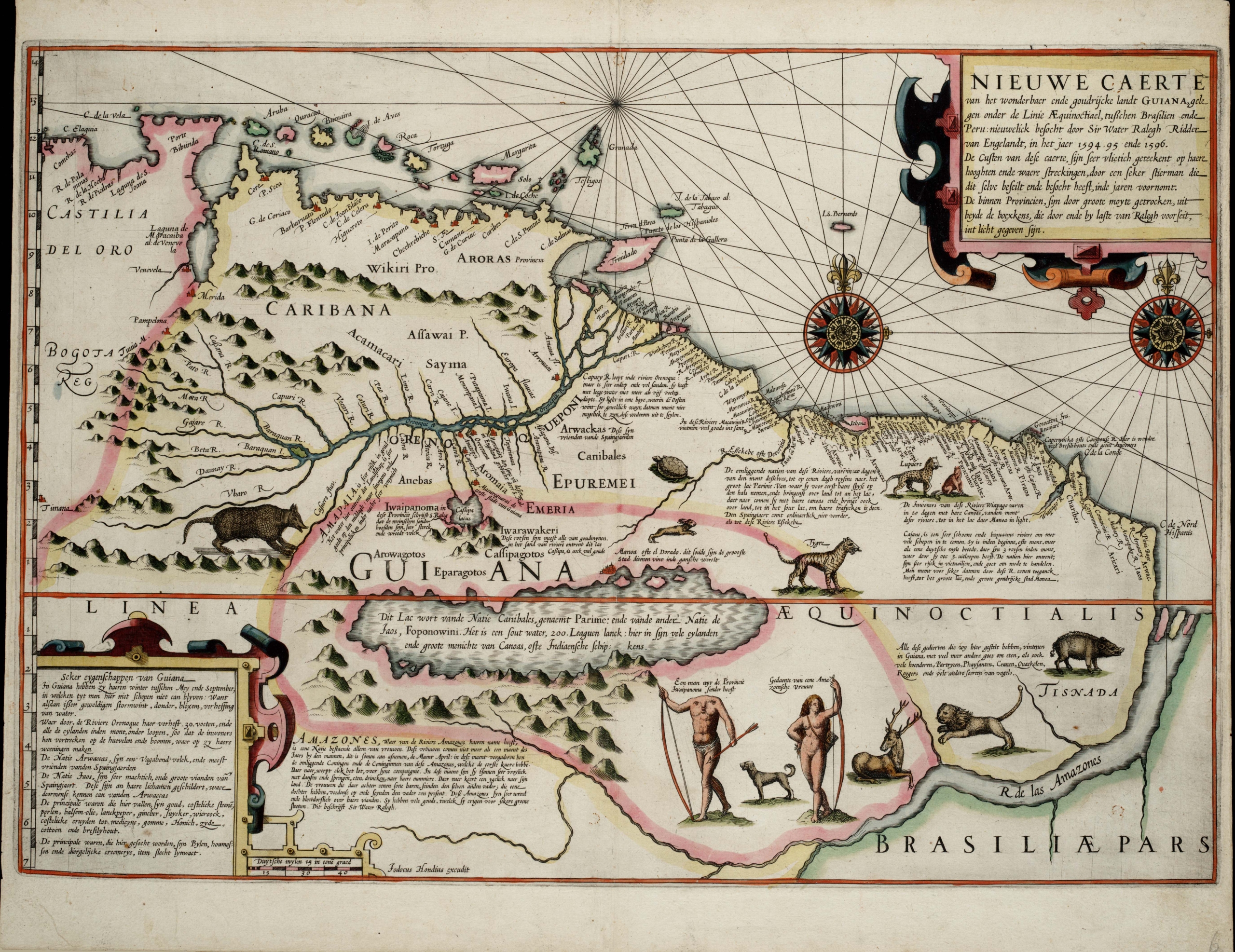

Few expeditions returned intact. Most dissolved into the forest, into competing accounts, into maps that turned into margins. Yet the story continued. Sir Walter Raleigh, writing decades later, shifted the location of El Dorado eastward, toward Guiana. His prose reframed it again – not as a local kingdom but as a continental system. The farther it was from reach, the more certain it became.

Meanwhile, the lake where it all began – Guatavita – was repeatedly drained in the centuries that followed. Engineers carved into the mountainside to lower the water level. A few objects were recovered. The gold was not vast. But the idea had already become its own reward.

What the Journey Left Behind

Today, El Dorado is preserved in fragments: museum cases of Muisca goldwork, colonial manuscripts, altered topographies. But more enduring is the route itself – the way the legend pulled people across forest and savannah, river and sierra, remaking space as it went.

The journey toward El Dorado was not a linear mistake or a failed treasure hunt. It was a convergence of imaginative systems, where European conquest met Indigenous cosmology and something new emerged. Not a city, not a vault of riches – but a geography of entanglement.

In this sense, El Dorado still exists – not as a place, but as a terrain shaped by pursuit, misunderstanding, adaptation, and exchange. It endures in the landscape’s layered names, in the paths now repurposed for roads and rivers, and in the historical memory of a continent marked by routes once walked in search of what was never there, and never absent.